What should Murtagh have worn? Thoughts male clothing in Outlander’s 1760s North Carolina

Updated in November 2022, after some thought... And in April 2024, after more thought..

I’ve always loved the 20th century clothing in Outlander. Whether it’s 1940s, 1960s or 1980s, it always seems perfect. And Accurate. Almost as good as my favourite period costume drama, Mad Men, in fact (yes, Mad Men is a period costume drama!). Here are a few examples of how good the 20th century costumes have been throughout Outlander’s six and a half series.

Figure 1: Frank & Claire (if memory serves me right this is just after they get married), pre- WW2. Image accessed from https://www.imdb.com/title/tt3627460/ on 3rd April 2024.

Figure 2: Frank is late 1960s personified here! Absolutely love his outfit here! Both of my grandfathers had glasses just like those too. Image accessed from https://claireandjamie.com/2020/10/23/outlander-book-3-chapter-19/2/ On 3rd April 2024

Figure 3: My nan actually had the blouse Brianna is wearing in the 1970s/1980s - probably a Marks and Spencers purchase I would have thought! - so yep, love this one too. I love the way Roger is looking at Bri in this one too :-) And my nan got the Radio Times every week. Image accessed from https://www.radiotimes.com/tv/drama/outlander-season-7-episode-6-roger-foe-surprise-twist-newsupdate/ On 3rd April 2024.

However, there has not been as much attention to historical fact for the eighteenth century costumes, and there has been more artistic license involved. That is all fine, unless folks take the costumes (& some storylines) to be accurate representations of historical dress and events (which some aren't). One of the main tensions for me in Outlander the TV series is the confusion it creates between what is fantasy and what is historical - and I still feel (in November 2022) that this is one of the major failings of the show. And what is considered 'costume' and/or historically-inspired. It is one thing to take creative licence with how someone who actually lived is portrayed (as Diana Gabaldon herself has said, only an idiot would think they were accurately portrayed), but turning one part of the the show into a very accurate representation of period costume (in this case 20th century) and then the other part not, really can be a bit disheartening.

Figure 4: Collage - Pretend Jacobites v. Real Jacobites: Bonnie Prince Charlie (in a sewn wool beret, nothing like the silk velvet bonnets he wore during the ‘45) Jamie (least we say about the leather coat the better) and various ‘Jacobite soldiers’ in the top image. Actual Jacobite prisoners painted by David Morier (detail from Morier’s Incident in the Rebellion). There was not a blue bonnet in sight in Outlander’s Culloden episode (except the prince’s).

Murtagh’s colonial clothing

TV Murtagh is one of my favourite characters. Despite his very full (and historically inaccurate) beard, Duncan Lacroix did such an amazing job with him and developed the character way beyond what was written about him in the books. I know I’m not alone in loving his character in the TV series, either. This is one of the costumes I have not enjoyed, in fact it’s really annoying to watch, simply because of the false narrative it perpetuates about tartan and the Act of Proscription (I've already written a blog post about the Act of Proscription).

Figure 5: Murtagh in North Carolina. Look at the state of that neckcloth! There’s absolutely no way any man went around with neckcloths that dirty (or fake dirty) in the 18th century, even if they were single. As for the scraps of tartan pinned on with a 19th century luckenbooth… Image accessed from https://outlander.fandom.com/wiki/Murtagh_Fraser/TV on 3rd April 2024.

1. The neck handkerchief / neck cloth (or neckcloath*)

There seems to have been some confusion during the first four series of Outlander about the colour of cloth worn around the men's necks in the 18th century and the amount of washing it received. It could be argued that pretty much all of the ones worn by main cast portraying Highlanders were given a dirty appearance, to look like they were hardly ever washed. Same goes for the shirts. In contrast, Claire's shifts - which were worn next to the body every day to soak up sweat etc. and also used as nightgowns- were always perfectly white.

As godfather to a land-owning laird (i.e.Jamie), Murtagh would not be at the bottom of the social ran but would have been of the 'middling' sort (I know he's a fictional character but hopefully you get my point!). This means he would have owned a number of neck cloths and that these would have been laundered on a regular basis. In her unpublished PhD, Dr Sally Tuckett discusses linen and perceptions of cleanliness and politeness in the eighteenth century Scotland: "the display of clean linen through shirts and other undergarments was vital to the maintenance of a respectable image" (Tuckett 2011: 61). So how were these shirts and other undergarments kept clean enough to portray a good impression?

Laundering in the eighteenth century

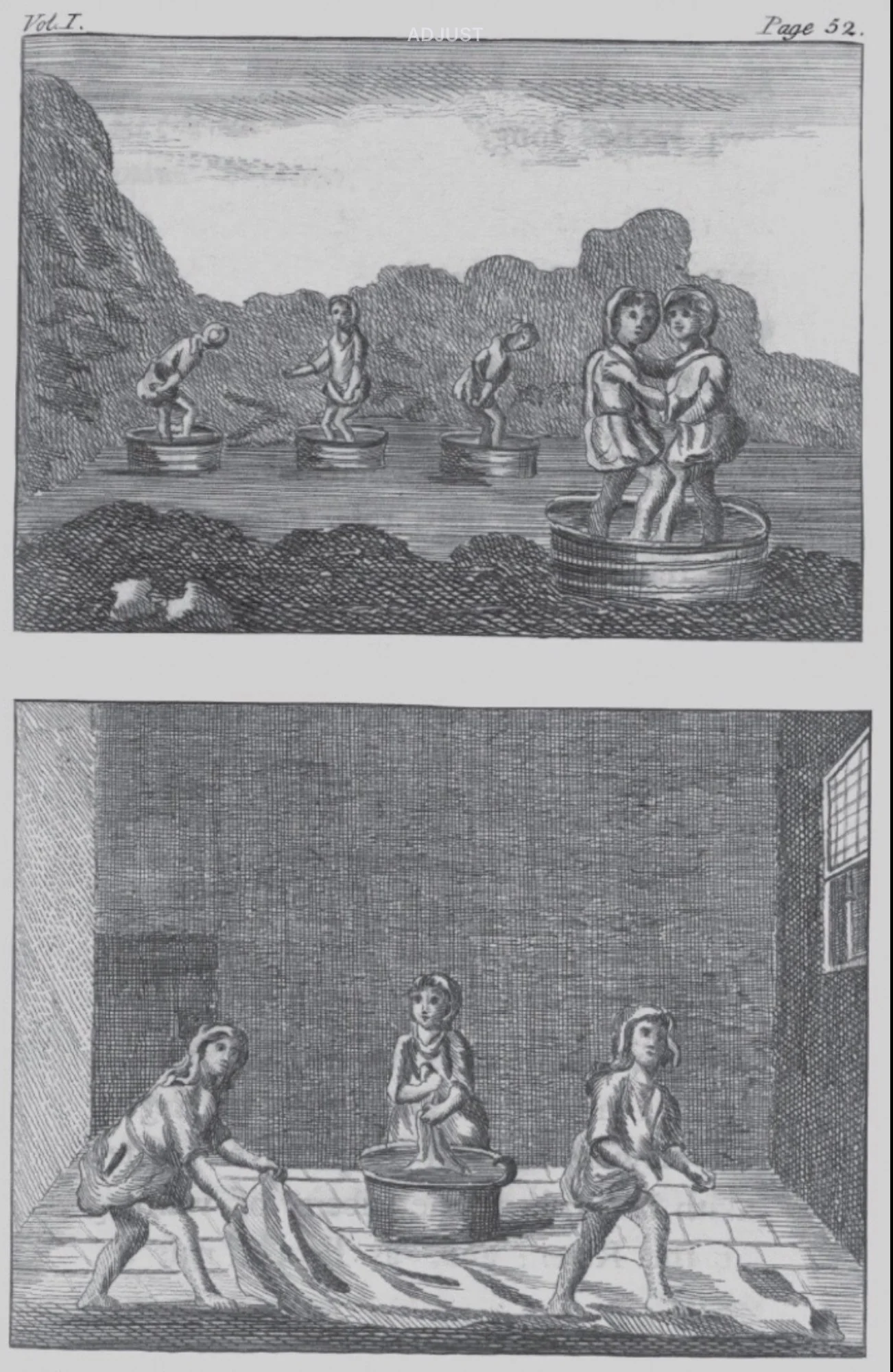

Figures 2 & 3: Laundresses at work in Burt, E. (1998) Burt's letters from the North of Scotland (loc 1207 of 5551, Birlinn: Kindle edition)

Edmund Burt described the washing of linen by women in the Highlands in the mid 1720s:

‘Before I leave the bridge, I shall take notice of one thing more, which is commonly to be seen by the sides of the river (and not only here, but in all the parts of Scotland where I have been), that is, women with their coats tucked up, stamping, in tubs, upon linen by this way of washing; and not only in summer, but in the hardest frosty weather, when their legs and feet are almost literally as red as blood with the cold; and often two of these wenches stamp in one tub, supporting themselves by their arms thrown over each other’s shoulders.’

Burt E. (1998: loc 1207 of 5551, Kindle edition).

Although Burt doesn't mention it, what the laundresses were doing on the banks of the River Ness was but one stage of the laundering process. He also doesn't mention the process of bleaching in the sun which was done in nearby fields.

Here's a link to an excellent presentation detailing how clothes were washed in the 18th century. "Bucking", which is referred to in the presentation, was in use from the middle ages to bleach fabric until the discovery of chlorine in the late eighteenth century. Aged urine produces ammonia - none in fresh urine- which was essential to clean cloth (it was also used to set dyes into wool before weaving and there is some anecdotal evidence that aged (not fresh) urine was used to waulk woollen fabric before the widespread introduction of soap; Claire peeing in a tub for imminent use in episode 105 is incorrect).

The fourth series of Outlander, Drums of Autumn, is set in pre-revolution North Carolina (I can understand why Diana Gabaldon chose to move the story there after reading about the history of North Carolina, again another wise choice by Herself).

I was delighted to find a travel journal from an eighteenth century Scotswoman, Janet Schaw, who visited Wilmington in the mid 1770s and therefore gives us a contemporary description of the town and activities which happened there. You can read her Journal of a Lady of Quality; Being the Narrative of a Journey from Scotland to the West Indies, North Carolina, and Portugal, in the years 1774 - 1776 with excellent notes here. This is what she had to say about the washing of laundry in North Carolina in 1775:

‘As soap and candle are commonly a joint manufacture, I will now mention that article, which they have here very good, as they have the finest ashes in the world. But when you have occasionally to buy it, however, you meet only with Irish soap, and tho' some house-wives are so notable as to make it for themselves, which they do at no expence, yet most of them buy it at the store at a monstrous price. They are the worst washers of linen I ever saw, and tho' it be the country of indigo they never use blue, nor allow the sun to look at them. All the [cloaths] coarse and fine, bed and table linen, lawns, cambricks and muslins, chints, checks, all are promiscuously thrown into a copper with a quantity of water and a large piece of soap. This is set a boiling, while a [] wench turns them over with a stick. This operation over, they are taken out, squeezed and thrown on the Pales to dry. They use no calender; they are however much better smoothed than washed. Mrs Miller offered to teach them the British method of treating linens, which she understands extremely well, as, to do her justice, she does every thing that belongs to her station, and might be of great use to them. But Mrs Schaw was affronted at the offer. She showed them however by bleaching those of Miss Rutherfurd, my brothers and mine, how different a little labour made them appear, and indeed the power of the sun was extremely apparent in the immediate recovery of some bed and table-linen, that had been so ruined by sea water, that I thought them irrecoverably lost. Poor Bob, who has not seen a bleaching-washing since a boy, was charmed with it, and Mrs Miller was not a little pleased with the compliments he made her on it. Indeed this and a dish of hodge podge she made for him have made her a vast favourite, and she has promised him a sheeps' head. But as she rises in the Master's esteem, she falls in that of the Mistress, who by no means approves Scotch or indeed British innovations.’

How frequently was the laundry done in the 18th century? Woodville Plantation, a late 18th century in Pennsylvania which is now a working museum, has published an excellent article about the wash day, which was always a Monday. Laundry was done weekly, just as it was by my grannies (I don't know about you, but I do laundry every day thanks to my wonderful washing machine). Here is a link to a great wee blog post from the lovely Two Nerdy History Girls about personal hygiene and cleanliness of linen in the 18th century (personally I think we could describe both Murtagh and Jamie as middle class).Here is another excellent link if you're interested in learning more about laundering in the 18th century; the fantastic 18th century notebook

Figure 4: At least Jamie and Murtagh has clean linen in Paris! Image accessed from https://outlander.fandom.com/wiki/Murtagh_Fraser/TV On 3rd April 2024

How many neckcloths?

It won't surprise the reader that a number of garments someone owned depended on how much money the person had, pretty much as it is today.

For her PhD, Sally Tuckett undertook an in-depth analysis of eighteenth century (Scottish) death inventories, which listed absolutely everything a person owned;

‘As men of varying social status wore similar basic garments – breeches, waistcoat, and coat or jacket – social status was indicated through the quality and quantity of the garments owned. With the increased emphasis on linen as a sign of respectability and status, the more shirts a person owned the greater chance they had of maintaining that respectable image. Of those men who had shirts listed in their inventories, most had at least two. The moveable goods of William Borthwick, a weaver from Newington near Edinburgh, were valued at just £4 10s 7d Sterling when he died in 1742. Included among his possessions, however, were three shirts. At the other extreme, George Preston, surgeon-major to his Majesty’s forces in Scotland, owned fifty-seven linen shirts when he died in 1749. [...]

Accessories could alter a wardrobe without the need of a large financial commitment – it was cheaper to acquire ribbons, ruffles, and buckles to update a garment and ensure a fashionable appearance, than it was to purchase a whole new outfit. Detachable shirt ruffles, stocks, and cravats were a means by which personal wealth, cleanliness, and respectability could be displayed. These items were common in the inventories and appeared among the possessions of men from a variety of social backgrounds.

James Braidwood, a candlemaker burgess of Edinburgh, owned a significant number of such items. Along with various suits, coats, wigs, and hats, Braidwood owned twenty-three “Linnen Necks”, twenty pairs of linen sleeves, twenty-seven muslin stocks, and three cambric cravats when he died in 1742. William Borthwick, noted above, had owned five cravats to go with his three shirts, demonstrating the ability of even “the working man to acquire petty clothing luxuries’

Tuckett (2011: 61-62)

Here's a link to another excellent blog post from the Two Nerdy History Girls and here's an excellent presentation from Ruth Hodges about what was worn around the neck by both men and women in British America during the revolutionary era.

2. The plaid, scrap of tartan & the luckenbooth

Since I first saw Murtagh back in Drums, I have been wondering why he wore an olive green plaid when (brightly coloured) tartan was available to him in the Colonies. Even more puzzling was the scrap of tartan pinned to his chest with a cast luckenbooth brooch.

Before discussing the wearing of tartan in the latter part of the eighteenth century in British America, I thought it would first be useful to mention references to tartan in the book Drums of Autumn by Diana Gabaldon. As fans of the show will know, Murtagh does not make it to the Colonies in the books (I am so glad that this has changed in the TV series), so I will refer to what Jamie wears... The following excerpt is taken from Chapter 12 of the book and is set at River Run, Jamie's Aunt Jocasta's plantation:

‘A Highlander in full regalia is an impressive sight–any Highlander, no matter how old, ill-favored, or crabbed in appearance. A tall, straight-bodied, and by no means ill-favored Highlander in the prime of his life is breath taking. He hadn’t worn the kilt since Culloden, but his body had not forgotten the way of it. ‘Oh!’ I said. He saw me then, and white teeth flashed as he made me a leg, silver shoe-buckles gleaming. He straightened and turned on his heel to set his plaid swinging, then came down slowly, eyes fixed on my face. For a moment, I saw him as he had looked the morning I married him. The sett of his tartan was nearly the same now as then; black check on a crimson ground, plaid caught at his shoulder with a silver brooch, dipping to the calf of a neat, stockinged leg. His linen was finer now, as was his coat; the dirk he wore at his waist had bands of gold across the haft. Duine uasal was what he looked, a man of worth. But the bold face above the lace was the same, older now, but wiser with it–yet the tilt of his shining head and the set of the wide, firm mouth, the slanted clear cat-eyes that looked into my own, were just the same. Here was a man who had always known his worth. ‘Your servant, ma’am,’ he said. And then burst into a face-splitting smile as he descended the last few stairs. 'You look wonderful,’ I said, hardly able to swallow the lump in my throat. ‘It’s none so bad,’ he agreed, with no trace of false modesty. He arranged a fold over his shoulder with care. ‘Of course, that’s the advantage of a plaid–there’s no trouble about the fit of it.’ Gabaldon, Diana (1996: 180-181)

The word 'plaid' appears in Drums over sixty times, usually in reference to Jamie (seemingly he has at least three plaids - a red and black one given to him by his aunt Jocasta which had belonged to her deceased husband, a crimson one and (at least) one made from a dark tartan. Other men also wear plaids in the book. None are described as being a plain, drab colour.

In my research for this blog post, I came across an incredibly interesting article discussing a law passed in South Carolina in 1735 about how Scottish tartan was used to dress slaves and those who worked on the ships. Sumptuary laws had been used by the British kings and queens for hundreds of years, basically to make sure that folks knew their place (or, as in Elizabeth I's case, to protect English workers' jobs by making it illegal to wear imported items). I'm not going to write out the name of the 1735 South Carolina Act as it's rather disgusting, but to summarise the law was all about slaves knowing their place by only being allowed to wear the poorest of fabrics.

Throughout the 18th century, tartans and other fabrics produced in Scotland were an important part of the trade between Britain and her colonies. Loranger and Sanders explain the trade thus:

‘Textiles were one of the pillars of England and colonial America’s slave trading economy. In fact, the American Colonies had become one of England’s greatest customers, as they represented a distinct piece of what has been termed the “Triangular Trade.” Gold bullion and manufactured goods left England bound for India’s textile manufacturing centers and also to Western Africa’s slave trading centers. These economic inputs provided the fuel necessary to procure goods, such as, inexpensive Indian Madras textiles and humans/slaves, which would then leave India and Africa bound for the plantations of the United States and Caribbean islands. Ships returning from the Americas to England would then supply raw materials, such as sugar and cotton, to fuel English industries, thus completing the cycle. By 1773, America would consume approximately one quarter of products that were made in England.’ Loranger and Sanders (2016: 684)

In an article published in the William and Mary Quarterly in 1945, Calvin B Coulter Jr discussed the trade from Glasgow with British colonies during the 18th century:

‘Glasgow's incoming commerce was based on sugar and rum from the West Indies and tobacco from the American plantations, with English capital providing much of the wherewithal to trade. In return, Glasgow shipped the native products of Scotland to the new world. Many of these did not differ substantially from those of England, but some were special to the country. Chief among the latter were many plaids or tartans which the Scots made in the Lowlands from Edinburgh and Stirling to Glasgow. Scottish osnaburgs, which were cheaper than the German ones and provided much of the summer clothing of the slaves, were manufactured around Glasgow. Plaid hose were made throughout the country from the Orkneys to the English border.’ Coulter, C (1945: 298)

Even though the Act of Proscription was enforced in Scotland on working class men and boys, it was never enforced on the upper classes during the entire time it was law. The whole thing about Murtagh keep a scrap of his original plaid secretly hidden I am afraid is a reworking of what would have happened and certainly does not warrant the importance it has in this costume. Murtagh, quite frankly, would have done what the 50,000 or so Highlanders who left for the Colonies did after Culloden, even if they were indentured for the first five to seven years of their time in America; purchased new ones in the New World as soon as circumstances allowed. I highly doubt that by 1768-1770 he would have been without a brightly coloured plaid - which was probably only worn for special occasions by then as men in the Colonies tended to wear breeches, even the men from the Highlands, for everyday wear- and walking around with a scrap of a pre-Culloden tartan pinned to his chest.

I have been lucky enough to see and hold a number of luckenbooth brooches, including Isabella MacTavish’s luckenbooth from the late 1770s/early 1780s as well as a number of luckenbooths (and penannular brooches) in the collection of the West Highland Museum in Fort William. I can therefore tell the difference between a luckenbooth which was made in the 18th century and one made later (they look rather different). Here's a nice article on luckenbooths from the New York Times, by the way. One of the main differences which is easily noticed is the fineness of the pin; earlier brooches have larger pins (which only became more refined in the Victorian era). Another difference is the engraving. Finally, the type of casting is important as well; the more finely cast a brooch is, the newer it is. The image below from the Wiki page on luckenbooths should explain my point here quite nicely. Brooch A is typical of a luckenbooth from the 1760s-1790s ( B and E are 19th century, C and D 20th century)

Figure 4: Scottish Luckenbooth brooches, 18th - 20th century (accessed from here on 26th April 2019)

Figure 5: close up of Murtagh's chest. See what I mean about the Luckenbooth? (close up of Figure 1, accessed from (image accessed from https://outlander.fandom.com/wiki/Murtagh_Fraser/TV on 24th April 2019

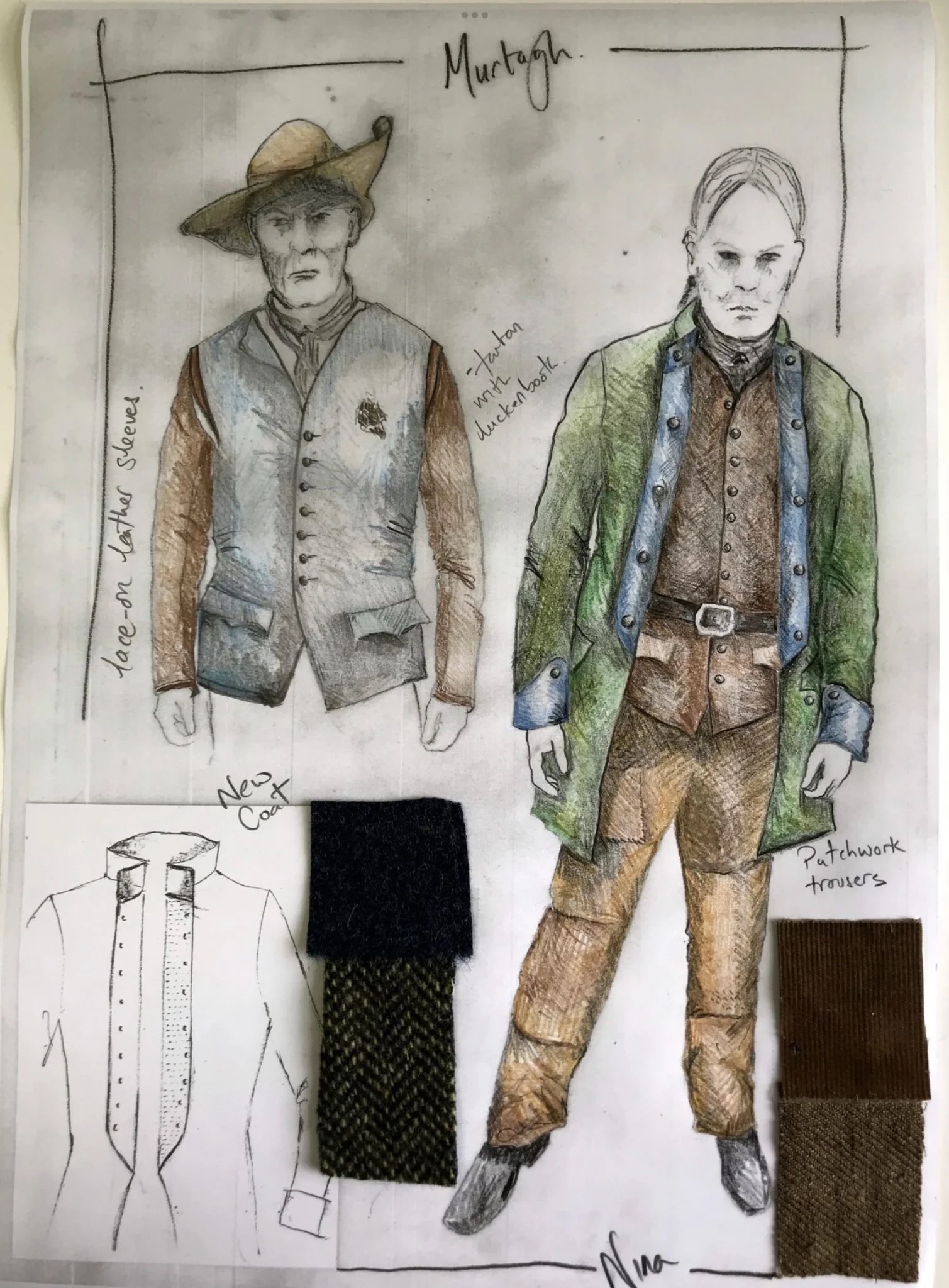

I'm going to finish this section of this blog post with the original design for this costume, which was shared on an 'official' Outlander website for fans [which seems to no longer be in existence in April 2024]. Costume designer Nina Ayers said the following about this costume:

‘On designing Murtagh's costume, Co-Costume Designer Nina Ayers said, "Murtagh epitomises the blend of European settler and Native American dress. As a Scot, he has retained the kilt in a lot of scenes but he also wears the local leggings. He also wears the swatch of his own tartan on a pin over his heart. This, he has had since his days imprisoned at Ardsmuir, a piece of home and Scotland he carries with him at all times.’

Accessed from here on 26th April 2019.

Figure 6: Nina Ayer's original design for Murtagh's costume in Drums of Autumn (accessed from here on 26th April 2019).

Murtagh wouldn’t have had it pinned on his chest with a 19th century brooch, but rather it would have been carried in his sporran. Or maybe sewn into the lining of a waistcoat. I know it’s a TV show, but …

So what was actually worn in Colonial America in the late 1760s/early 1770s?

Since publishing this post in 2019, the brilliant Michael Ramsey of Colonial Williamsburg has published a great blogpost on what was worn in Virginia in the 18th century: https://www.colonialwilliamsburg.org/learn/deep-dives/scottish-dress-18th-century-virginia/ . He also published an article in the Association of Dress Historians in 2019, which you can read here: https://dresshistorians.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/JDH_Autumn_2019.pdf . Both are fantastic and thoroughly researched.

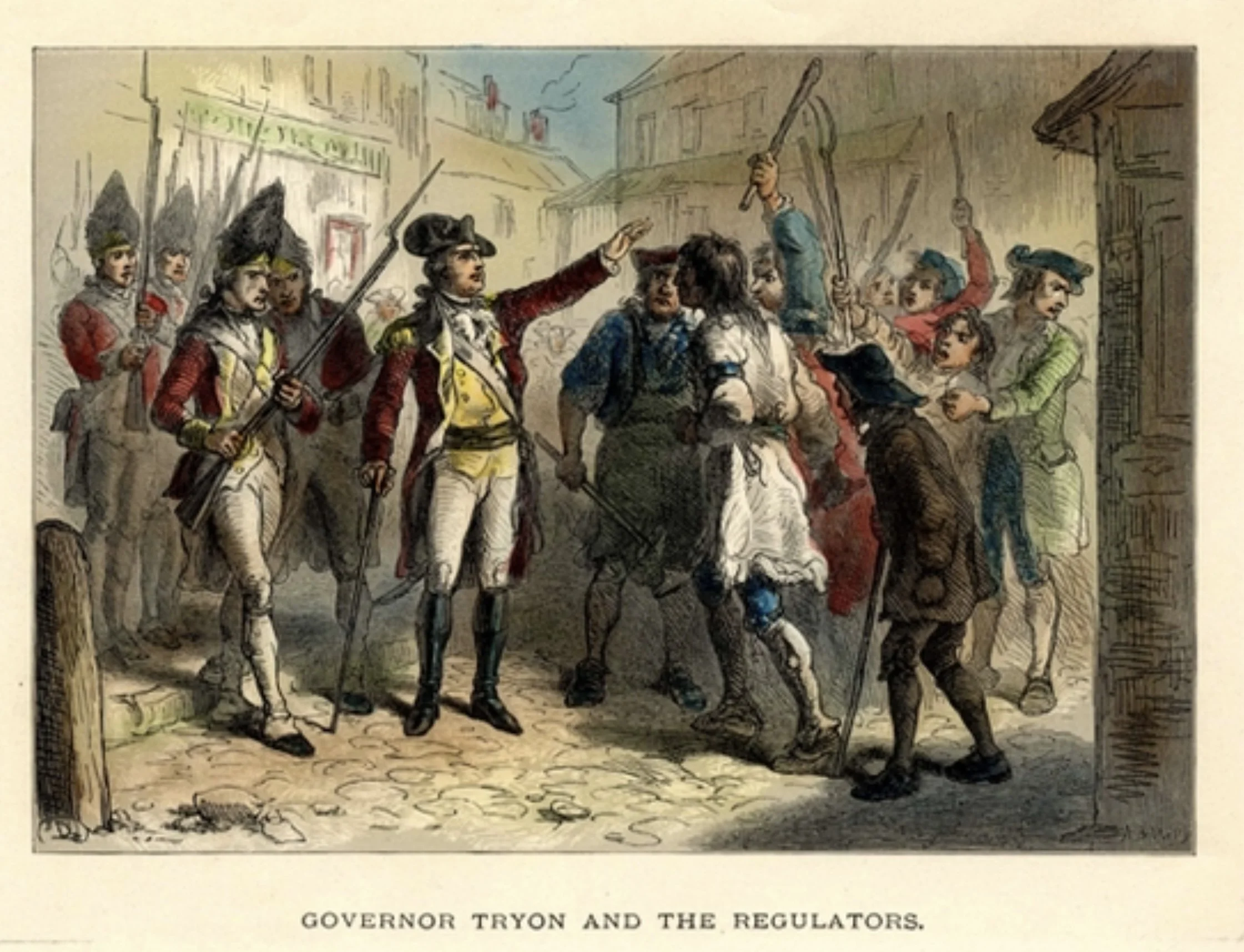

There are some contemporary prints of the Regulators from the time (Murtagh is a leader of the Regulators in the fourth series of the programme):

Figure 7: Tryon confronting the Regulators, 1771 (accessed from here on 26th April 2019)

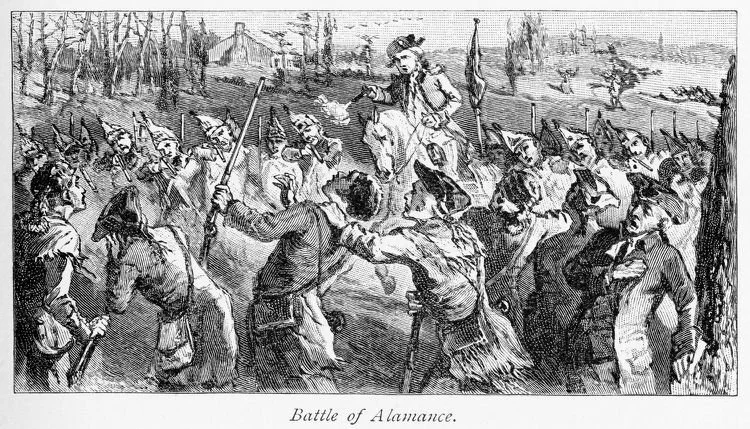

Figure 8: A scene from the Battle of Alamance, 16 May 1771. Image accessed from https://www.thoughtco.com/regulator-movement-history-and-significance-5076538 On 3rd April 2024.

Above in figure 8 is a scene from the Battle of Alamance, which was fought between Governor Tryon’s British forces and local Regulators on the morning of 16th May 1771. A Quick Look at the Outlander Wiki page for Murtagh tells me that he dies in May 1771 in the TV series (it’s been a while since I’ve watched it), so the dating of the above scene seems perfect. If we take the chap on the far right with his hand over his heart (has he just been shot?) as a perfect example, then we can answer our original question.

Murtagh would have worn a black tricorn hat, a white neckcloth, a coat reaching mid-thigh to above knee, probably in a worsted cloth, presumably a white linen shirt, white stockings, worsted breeches and a waistcoat. Although said waistcoat could well also have had a worsted front (it definitely would have had a linen back), perhaps - just perhaps- it had a tartan front.

References

Coulter, Calvin B. “The Import Trade of Colonial Virginia.” The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 2, no. 3, 1945, pp. 296–314

Gabaldon, Diana (2011) Drums of Autumn (Kindle edition)

Loranger, David & Sanders, Eulanda (2016) Sumptuary Synergy: British Imperialism Through the Tartan and Slave Trades Crosscurrents: Land, Labor, and the Port. Textile Society of America’s 15th Biennial Symposium. Savannah, GA, October 19-23, 2016.

Tuckett, Sally (2011) Weaving the Nation: Scottish clothing and textile cultures in the long eighteenth century (unpublished PhD, University of Edinburgh)