Betty Burke

Figure 1: Etching of Prince Charles Edward Stuart as Betty Burke (1747). Engraving printed in the Iberian Illustration, 1885. Accessed from https://thestuartkings.tumblr.com/post/22844083502/prince-charles-edward-stewart-bonnie-prince On 16 November 2022

Following on from my 2022 project about Flora Macdonald’s wedding outfit, I recreated the outfit worn by Prince Charles Edward Stuart (PCES) for four or five days in June/July 1746 when he wore women’s clothes and assumed the identity of Betty Burke, an Irish spinning maid. I spent almost a year throughly researching every thing I could possibly learn about this outfit, how and where it was created and by whom. It came about from reading Flora Fraser’s excellent biography of Flora Macdonald (in which it was documented that Flora was an accomplished seamstress/dressmaker), and wanting to honour hers and Lady Clanranald’s ingenuity under extreme pressure. My inspiration for this project also came from being aware of various portrayals of this outfit and event, and also knowing about the piece of fabric inside volume 3 of Lyon in Mourning.[1]

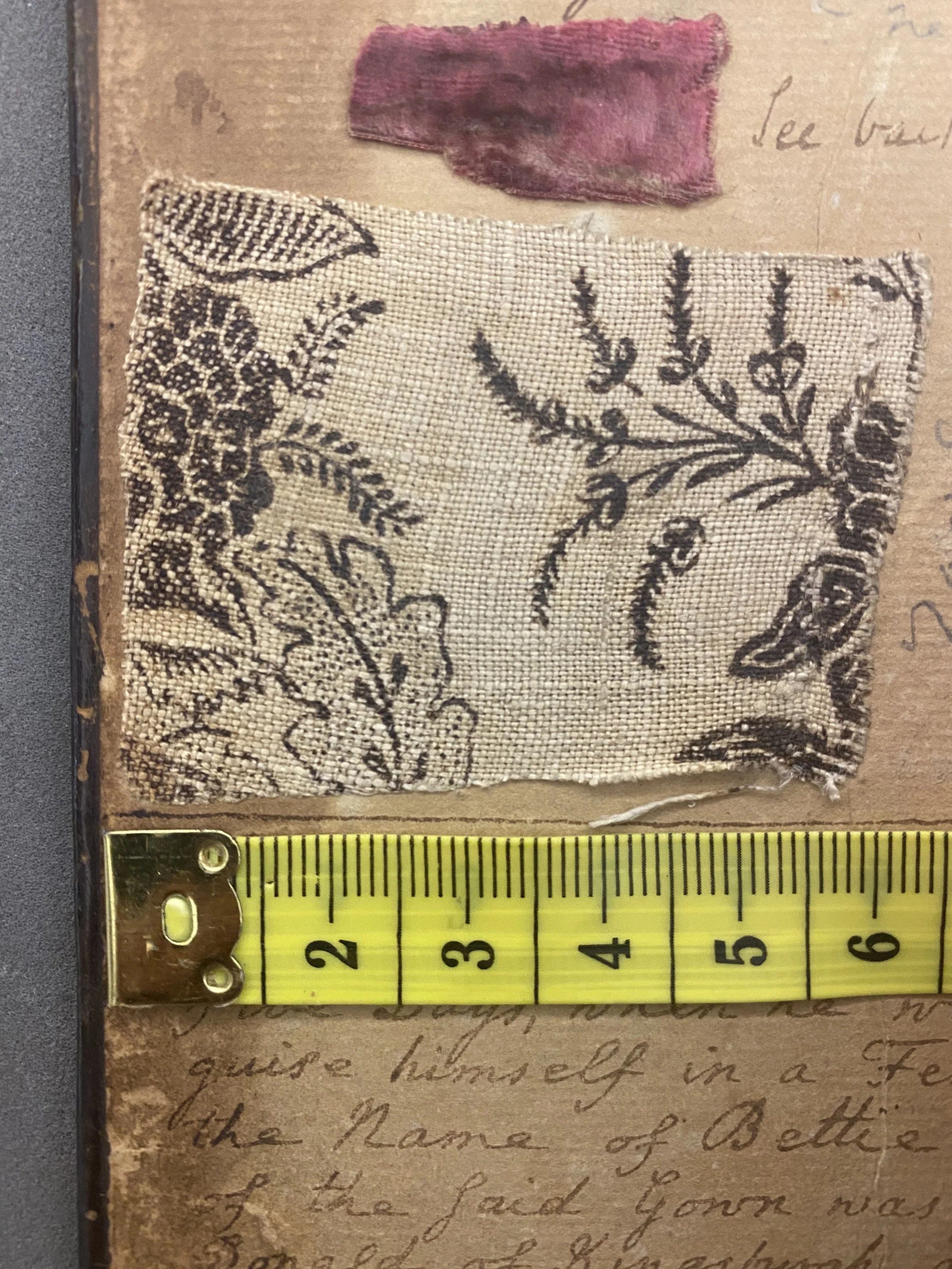

Figure 2: Inside cover of volume 3 of Lyon in Mourning. Photo taken by Jo Watson with full permission of the National Library of Scotland. Stitching holes are visible on the right hand side and give a measurement of 12 stitches to the inch (valuable sewing information). The print used to be purple, but due to the use of iron in the printing process it has become black over time.

Inside the back cover of volume 5 of Lyon in Mourning, there is a sketch of the shoes which the prince wore and two tiny pieces of the leather straps. The two scraps of leather were given to Bishop Forbes by Flora Macdonald. These shoes are in the possession of the Blair Oliphants of Ardblair Castle and were last on display at the National Museum of Antiquaries of Scotland in 1985 in the ‘I am come home’ exhibition. A catalogue of this exhibition is in the collection of the National Library of Scotland and contains important information about, as well as a photograph of, the shoes. A fascinating article by Robert B K Stevenson on the shoes was published in the journal The Review of Scottish Culture, volume 6 (1990), pages 77-80, which include very important information not only on the provenance of the shoes but also on their dimensions and how the shoes were constructed.

Figure 3: the two ends of the straps as preserved (or not!) inside Lyon in Mourning. Photo: author, Shared with permission of the National Library of Scotland

Figure 4: The shoes the Prince wore as Betty Burke, minus the straps (which were cut off and given to people as momentos). Photo: Professor Hugh Cheape, shared with permission.

In addition to the piece of printed linen on the inside cover of Lyon in Mourning, which was given to Bishop Robert Forbes by Flora Macdonald’s future mother in law, there are three accounts of what clothes formed the prince’s outfit. One is from the Kingsburgh Manuscript, which I discuss a bit further on. The other two are below.

Lady Clanranald begged of his royal highness to try on his new female apparel, and after mutually passing some jocose drollery concerning the sute of cloaths, and the lady shedding some tears for the occasion, the said lady dresses up his royal highness in his new habit.1 It was on purpose provided coarse as it was to be brooked by a gentlewoman’s servant. The gown was of caligo, a light coloured quilted petticoat, a mantle of dun camlet made after the Irish fashion with a cap to cover his royal highness whole head and face, with a suitable head-dress, shoes, stockings, etc.

Lyon in Mourning, page 330 (Captain Alexander Macdonald’s journal)

Captain Alexander Macdonald was not only Flora’s cousin but was also the renowned Gaelic poet - Alasadair mac Mhagistir Alasdair- and was the prince’s Gaelic teacher throughout the ‘45 campaign. He went into hiding after Culloden, but did indeed meet Bishop Forbes in 1747.

3rd [question] what Cloaths had Sinclair [PCES] on, also this Flora Mackdonald.

3 rd [response] Sinclair had on a woman’s Calicoe gown, a Camblet yellow long Cloak a big Cape to It of the Same. Flora had a long jacket of English blue Cloath, a Silk black hood.

Royal Archives, RA CP/MAIN/68/xi:37/30, Rowry Macdonald: Declaration , 9 July 1746

A mantle of dun camlet

The next task was to look in the Dictionary of the Scots Language online (www.dsl.ac.uk) and the Oxford English Dictionary to get some clarity on the ‘mantle of dun camlet made after the Irish fashion with a cap to cover his royal highness whole head and face’. I was rather intrigued by the ‘after the Irish fashion’ and ‘with a cap’. I looked in the Dictionary of the Scots Language and this was what it came up with

‘B. FREQ[uently] applied to a kind of plaid or blanket worn as their principal garment by Highlanders and Irishmen.’ (https://dsl.ac.uk/entry/dost/mantill_n_1)

For a woman, this means the arisaid, not a mantle in the English sense of a coat - or at least I thought it did. It was recorded that the prince got very annoyed in the boat with the mantle falling off his head all the time, and indeed arisaids can do that. However, a discussion with Professor Hugh Cheape about Benbecula, trade with Ireland and what Macdonald could possibly have meant by a mantle after the Irish fashion did indeed confirm that it wasn’t Irish as in Erse as in Highland (as was frequently used by Lowlanders at the time) but indeed it was Irish as in from the island of Ireland. I’m afraid that I’ve not really studied historical Irish fashion much, and sadly there is not much in print of it either. There are two out of print books on it, which Hugh has copies of in his personal library, and that is about it (I’m hoping that the fantastic dress historian Laura Fitzchary will do something to correct this!). Anyway, here’s basically what Macdonald meant. Here’s a fantastic blogpost on the 16th century brat which eventually became a regionalised cloak, with each region of Ireland having its own variation.

Figure 5: A 19th century ‘colleen’ in a Kinsale cloak. Accessed from File:Colleen in Kinsale Cloak.jpg - Wikimedia Commons on 5th April 2024

So what was dun camlet?

Dun is a Scots word which refers to a dull brown (https://dsl.ac.uk/entry/dost/dun). Scottish language expert Àdhamh O’Broin has described it to me as a khaki/dark tan colour. According to Samuel Johnson, camlet was mainly woven from silk and wool, and the OED definition also gives examples of it being woven from long wool, which would produce what we know as a worsted cloth today (similar in a structure to 18th century tartans, which were also made from long wools and worsted yarn). The silk would have not only provided softness, but also strength and was most likely used as the warp thread. Norwich was the centre of manufacture of this fabric in the mid 18th century.

Figure 6: A stock image of a Shetland sheep. The Shetland is a living descendant of the Scottish Dunface sheep which was common in Scotland in the 18th century. The ‘dun’ wool used for the prince’s cloak could well have been a natural shade of a sheep with a similar fleece.

The calico gown

As shown above, a small piece of the actual gown survives. With permission of the National Library of Scotland, I took photographs of it and it was digitally manipulated into a pattern which was printed digitally on fabric. I believe the original pattern was larger than what survives in Lyon in Mourning based on similar printed calico designs of the period, and my research to try and find a larger piece of the pattern continues. The calico was reprinted by Stewart Carmichael of Bonnyhaugh, near Leith, in 1748-9 for Jacobite ladies to demonstrate their Jacobite beliefs in a secretive manner after he received a full piece of the pattern from Flora Macdonald’s mother in law. Dr James Burton of York, who was a fellow prisoner of Flora in London after the Uprising, later wrote that Flora had seen the Carmichael reprint (of which he ordered many yards for dresses to be made for his wife and other Jacobite ladies) and said it was a perfect match. I have tried everywhere I can think of to find some of Carmichael’s fabric, to no avail.

Figure 7: The gown after two days of sewing at Nunton House, June 2023. I still had the cuffs to apply and some hemming to do on the skirt. Photo” Jo Watson, June 2023

Light coloured quilted petticoat

This is the only garment in the Betty Burke outfit which most definitely was not made in the 4.5 days available to the ladies to sew, but it seems highly likely that a petticoat which already existed was altered to make it longer. There are examples of this having been done in museum collections and the alteration would have been hidden by the apron. We now know from the Kingsburgh manuscript that this was made from ‘coarse’ wool (‘coarsen’ materials being chosen as suitable for a servant’s clothing; see page 5 and the quote from Lyon in Mourning to corroborate this). I chose fine and common shalloon from Kochan & Philips to make the petticoat. It was quilted with a thin layer of carded wool fleece. I have written a separate blogpost just on the petticoat, which you can read here.

Figure 8: My friend Carolyn (who came over to Benbecula with us) sitting at the dining table while I took a break from sewing the petticoat panels together. I had planned to have this petticoat entirely finished before arriving at Nunton, however eight days of Covid prevented that and therefore it was finished at Nunton. The sewing supervisor looks on from the window seat. Photo: Jo Watson, June 2023

The Kingsburgh Manuscript

In 1802, Anne McAllister who was the sister of Flora’s husband, Allan Macdonald, dictated her memoir of when Prince Charles Edward Stuart visited the Isle of Skye. This was clearly written for her children, as there are frequent references to ‘your mother’ and so on. This manuscript is in the private possession of her descendants at Glenbarr Abbey in Argyll. I have been told by the Clan MacAllister historian that Lady MacAllister is of advanced years and in poor health, but I do hope to be able to see the original manuscript at some point. Thankfully the manuscript was seen by Rev. A MacDonald in 1930 and published in his Memorials of the ’45 as an appendix. Pages xxiv – xxv give us an excellent description of Prince Charles Edward’s Betty Burke dress, from someone who clearly knew how to make clothing. I think it is important to include Anne MacAllister’s own description here:

The 28 June [1746]

Lady Clanranald begged of his royal highness to try on his new female apparel, and after mutually passing some jocose drollery concerning the sute of cloaths, and the lady shedding some tears for the occasion, the said lady dresses up his royal highness in his new habit. It was on purpose provided coarse as it was to be brooked by a gentlewoman’s servant. The gown was of caligo, a light coloured quilted petticoat, a mantle of dun camlet made after the Irish fashion with a cap to cover his royal highness whole head and face, with a suitable head-dress, shoes, stockings, etc.

Your mother brought the Prince a suit of your father’s cloths, the first she brought him he thought too fine as they had plated buttons, the next she brought him pleased him much and answered him as well as if they had been made for himself. He said it was hard he coud not see the gentileman he had robbed of his cloths; your grandfather told him he saw plainly he never coud travel in woman’s cloths; a short time before he left the house your mother came in to put on his dress as it was proper he should leave the house in the same dress he brought to the house, after putting on his gown and head dress, Madam you have forgot my apron, he says, smiling. The Prince dress was a printed goun, a coarse stuff petticoat and an old Camlet cloak, a linen apron, a musline cap - and a ribbon, and a coarse napkin, & cotton gloves - your grandmother made a bedcover of the goun, your mother got the gloves, Flora MacD got the apron which I myself saw. There was bits of the ribbon and cape sent to different families in the South, your grandfather kept the shoes. There was as many demands upon bits of them, your grandfather gave him a pair of his own shoes.

Flora MacD was not present when the Princes hair was cute, she was off for Portree to meet him there, it was your mother that cut his hair, it was your grandmother that proposed cutting his hair, which he was very happy to give her, his hair was very short it was at the back of his head they coud get it at any length, he always wore a wig, he had it in his trunk when he came to Kingsburgh and put on after he left the house when he dressed himself at the side of a hill near the house in your Fathers cloths your grandfather brought home his dress excepting the broun cloak which he buried in the shore, as every house was searched for his dress, Captin Ferguson told your grandmother his whole dress even the goun was hid in a bush by your grandfather til the search was over…

A MacDonald, 1930: xxiv – xxv

As can be seen from the above quote, not only does this information confirm what has been written elsewhere about various items of the dress, but it also adds incredibly useful other information. Perhaps the most important piece of information is that the petticoat was not made from silk, as I had originally expected, but was actually made from ‘coarse stuff’. Coarse in this sense means what we would today call heavier or thicker fabric, and ‘stuff’ is an eighteenth century term for worsted wool fabric. [2] Coarse stuff, which sometimes had a linen warp and worsted weft (known as ‘Linsey-Woolsey’) was predominantly made in Kidderminster in the 18th century, but could quite easily have been woven locally in the Outer Hebrides, or elsewhere in Scotland. Having lived in Benbecula myself for a few months, my guess is that it was locally produced (but I can’t prove that one way or another).

Figure 9: Getting Alex dressed in the ‘suitable head dress’. Image courtesy: Sandy MacCook/DCT

Coarse napkin and cotton gloves

A coarse napkin simply refers to a neckerchief attached over the shoulders, possibly from local spun & locally woven plain wool fabric. No doubt Lady Clanranald’s servants would have already had this at Nunton House. I ended up using a lovely linsey woolsey handkerchief from Burnley and Trowbridge as I was unable to purchase handspun, handwoven plain coarse fabric (and, admittedly, wanted to save some time!)

Figure 10: Making sure the neckerchief covers Alex’s Adam’s apple. Photo: https://www.pressandjournal.co.uk/fp/past-times/5989474/bonnie-prince-charlies-betty-burke-disguise-recreated-in-meticulous-detail/

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the term ‘mittens’ was not used in English until the mid to late 1750s (with the same meaning as we have for it today), and therefore accessories which covered the hands-and arms- were simply referred to as gloves (whether or not they covered the fingers or not). Woman’s mid-18th century mittens could be purchased readymade, made by a seamstress or quite easily by a lady themselves. Given his much larger than usual size, I think it quite likely that the mittens were made specifically for the Prince in the 4.5 days available to Flora and Lady Clanranald. I ended up using some leftover linen (leftover fabric was called ‘cabbage’ in the 18th century) to make the mittens, using a pattern from Burnley and Trowbridge.

The shoes

As seen above, we know exactly what the prince’s shoes for these few days looked like. My good friend John The Targeman made a fantastic replica pair of shoes for the project. Please go and like his page, and if you like targes then he’s your man! You can read a great interview with him in the Press and Journal here.

Figure 11: Composite image of a page of Lyon in Mourning, the shoes handmade by John and John outside Leanach Cottage at Culloden (in a jacket and bonnet made by me). Image: DCT Design, Jo Watson and John Stewart https://www.pressandjournal.co.uk/fp/past-times/6258421/bonnie-prince-charlie-betty-burke-shoes-recreated/

Underwear – petticoats, a muckle pocket and stockings

The petticoats may well have been ones which were already belonged to Lady Clanranald or her daughters, but were altered and enlarged to fit the prince. Although we know he was slim at this point in life (other items I have studied at the West Highland Museum belonging to him during the ’45 measure as him having a 26-28” waist and 36” chest), the average lady was a lot more petite and petticoats would have been needed to be lengthened. Initially I was going to repurpose the petticoat I made for the Flora Macdonald Wedding Dress project in 2022. This not only saves a lot of sewing time, but it also saves money. It makes absolute sense to me that this is what Flora and Lady Clanranald would have done. However, I ended up making a new petticoat as I wanted to still be able to use the Flora petticoat with the Flora gown.

Figure 12: Getting Alex dressed at Glenfinnan. Yes, I forgot the bag with my shoes, stockings, linen cap and mittens. Image courtesy: Sandy MacCook/DCT

I think it is highly likely that PCES wore a linen garment of some description next to his skin. Until I found out about the possibility of him wearing a waistcoat and breeches underneath, I presumed this would have been a woman’s shift. I’ve written a bit more about this in the ‘things to still make’ section which follows at the end of this post.

There is a reference to the prince wearing ‘muckle pockets’ underneath his Betty Burke dress. Information about pockets is available here: https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/womens-tie-pockets. At first I was unsure whether these pockets would have been really muckle (the Scots word for ‘big’) like side hoops, or a large embroidered pocket. I then found another reference which used pocket in the singular, so concluded that it was indeed one large pocket. Although feasibly a quick pocket could have been stitched from cabbage (the 18th century word for offcuts of fabric), I think it’s probably more likely that an existing one of the Clanranald ladies’ pockets was used. I decided to embroider one (I love embroidery) as I think it is quite likely that the Clanranald ladies also practised their embroidery on their pockets.

Stockings

We used these great silk stockings from Burnley and Trowbridge.

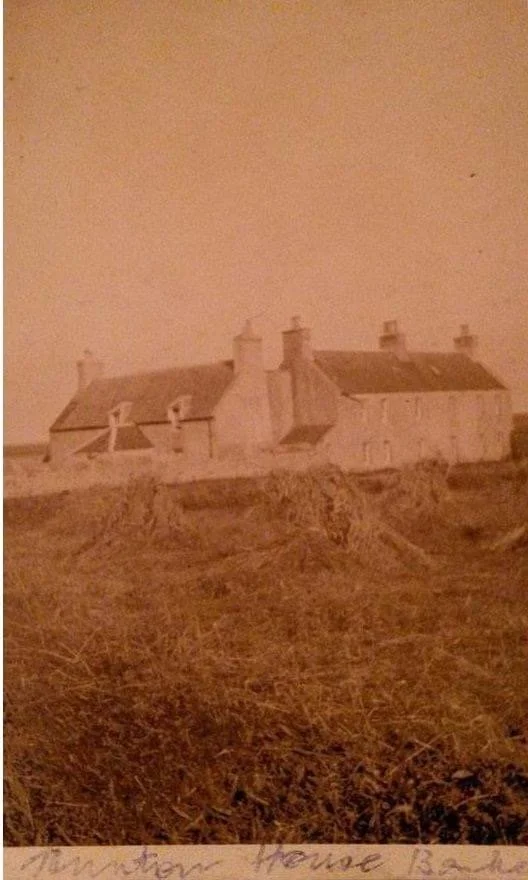

Figure 13: Nunton House at sunset. Photo: Donald MacPhee

Where I made the outfit: Nunton House, Benbecula

A very important part of the Betty Burke story is the fact that Flora Macdonald and Lady Clanranald made the outfit in 4.5 days (between the afternoon of 22 June – the morning of 27 June 1746) and that we know exactly where they made it – at Nunton House on Benbecula. Today Nunton House is part family home, part hostel. Their website is at https://www.nuntonhousehostel.com. Please do go and stay there; it is a wonderful place with lovely hosts.

An interesting short podcast is available to listen to here: https://soundcloud.com/user-742277911/the-bonnie-prince-and-nunton-house

I decided to recreate the making of the Betty Burke outfit in the place where the original was made for a number of reasons:

- There is a huge historical link which could be discussed; this indeed was on both BBC Alba’s An Là and in articles by the Press & Journal.

- This very much ties in with the Gaelic sense of dùthchas;

- Instead of making the outfit at home, which of little interest to the general public, making it in the place where the original was made adds an extra layer of interest

- Spirit of the Highlands is about the heritage of the whole Gàidhealtachd and a project taking place in another part of the region was important to me; not everything is in Inverness.

Figure 14: Nunton House in the 1920s. This is what the house looked like before the renovation, shortly after the Land Raids where four families moved into Nunton. Photo from Donald MacPhee.

Figure 15: The fireplace in the kitchen at Nunton House. This is where John MacLean, chef to the Clanranald, would have cooked for Flora and the prince. I sat next to this fireplace when sewing the clothing you see above in this blogpost. Image: Donald MacPhee

My experiment in making the clothing at the exact place (give or take a room; I was in the kitchen and Flora & the Clanranalds sewed in their parlour which was the other side of the wall) yieled some great insights. First of all, it rarely gets dark on Benbecula in June. I think there were maybe three hours of night and good amounts of light the rest of the time (being right next to the sea certainly helps with the luminosity). In the winter, you’re lucky if you get eight hours of daylight a day. Therefore, there is no way that Flora and the Clanranalds would have been able to put this entire outfit together in only four and a half days if they had been sewing at another time of year (eighteenth century seamstresses being heavily reliant on daylight for sewing and sewing by candlelight being difficult).

It really confirmed to me as well what was made in the four and a half days, and what must have been pre-made/repurposed:

Coarse linen shirt - the prince already had this on and it served as his underwear

Possible waistcoat and breeches - again the prince already had these on and would have been worn for warmth. The waistcoat is the only item I am unsure about; it would have been difficult to fit an eighteenth century open robe over both a shirt and a waistcoat (not impossible though)

Stockings - I think these were pre-made and probably were a silk pair which belonged to the Clanranald

Garters - definitely pre-made; they were the prince’s and brought over with him on campaign

Shoes - I think these were possibly made at the same time as the outfit, simply because they do not look like they had lots of wear and the prince had rather large feet for the time. There is a tale locally that he was shielded by a shoemaker and his wife on Uist when in hiding waiting to escape with Flora, so I think it is likely that the shoes were made then. They could also have been a pair owned by one of the Clanranald men.

Petticoats - I think these were pre-existing petticoats which were altered by adding length and possibly extending the waist. So partly pre-made, partly altered. This is something which wouldn’t take a competent seamstress that long to accomplish (it seems like something the younger Clanranald daughter may have been given to do).

Apron - Made during the 4.5 days due to the length required (it could well have been partly visible under the cloak). This would only have taken a day to make at the most.

Quilted petticoat - Pre-made, and possibly altered at the waist to increase length and width of waistband. This probably took about a day to day and a half.

Cotton mittens - definitely made during the 4.5 days. The prince was unusually tall (5’10”) and his arms and hands would have been larger than any female in the Clanranald household. They probably took about a day and a half to make.

Handkerchief - pre-made. It could well have belonged to one of the female servants.

Gown - definitely made during the 4.5 days. I imagine that two or three of the seamstresses worked on this together. It took me three full days to make one by myself, but Flora and Lady Clanranald would have made similar gowns before (as was common in the Outer Hebrides at the time). We know that Flora was a competent seamstress (there are accounts of her sewing on board the ship she was imprisoned on at Leith to pass the time in Lyon in Mourning).

Linen cap - made during the 4.5 days due to the size of the Prince’s head and the need to cover as much as his face as possible.

Cloak - We know from various accounts that it was a pre-made Irish cloak. Therefore I made the cloak long enough to be full length for the average woman’s height of the time (about 5’4”) which is why it is not full length on Alex.

So to summarise, the only garments which were made in their entirety during the 4.5 days were the linen cap, the apron, the cotton gloves and the gown. The petticoats were most likely adjusted by adding in extra fabric.

This project has helped correct the narrative on the prince’s Betty Burke costume and also demonstrates how useful experimental historical sewing can be.

Still to be made/found

I still have a couple of things to make to complete the outfit. These will be shown in public for the first time at the Grandfather Mountain Highland Games, North Carolina in July 2024.

Brooch

Finally, there is a reference in Jen Novotny’s PhD thesis on Jacobite material culture to a brooch being on display in the 19th century which was believed to have been worn by PCES when dressed as Betty Burke (Novotny 2013: 251). Although Flora’s descendants do indeed own a brooch worn by Flora, it seems highly unlikely that it is the same brooch which was on display which Novotny references as the description is completely different. I have attempted to find an image of the brooch, and will look at the exhibition catalogue next time I am at the National Library of Scotland to see if I can find out more information about who lent the brooch to the exhibition.

Buckled French velvet garters

There is a reference to the prince wearing buckled French velvet garters, covered on one side with white silk, in Flora Fraser’s Pretty Young Rebel (Fraser, 2022:141), which she had taken from Lyon in Mourning volume 1, xviii, page 112. It says that Flora’s younger half brother had left them in the Citadel in Leith (perhaps with Lady Bruce or Bishop Forbes himself?) and then had collected them when she was in Edinburgh. It is therefore quite important to include these garters in the costume. He also wore his wig while on the run from the British, however when he was dressed as Betty Burke this was put in Flora’s small travelling trunk. I find it quite amazing that a man on the run for his life took these items with him, and I think it demonstrates how important his appearance must have been to him.

‘Below these he wore his waistcoat and small cloaths’

The third section of the Kingsburgh manuscript was written by Matthew MacAllister, Anne MacAllister’s son, and he wrote of the Betty Burke dress:

The Prince’s dress was a printed gown, a coarse stuff pettycoat, an old blue [sic] Camlet cloak, a linen apron, a muslin cap, a coarse napkin over his shoulders, and coarse cotton gloves. Below these he wore his waistcoat and small cloaths.

(A Macdonald, 1930: xxxviii – xxxix)

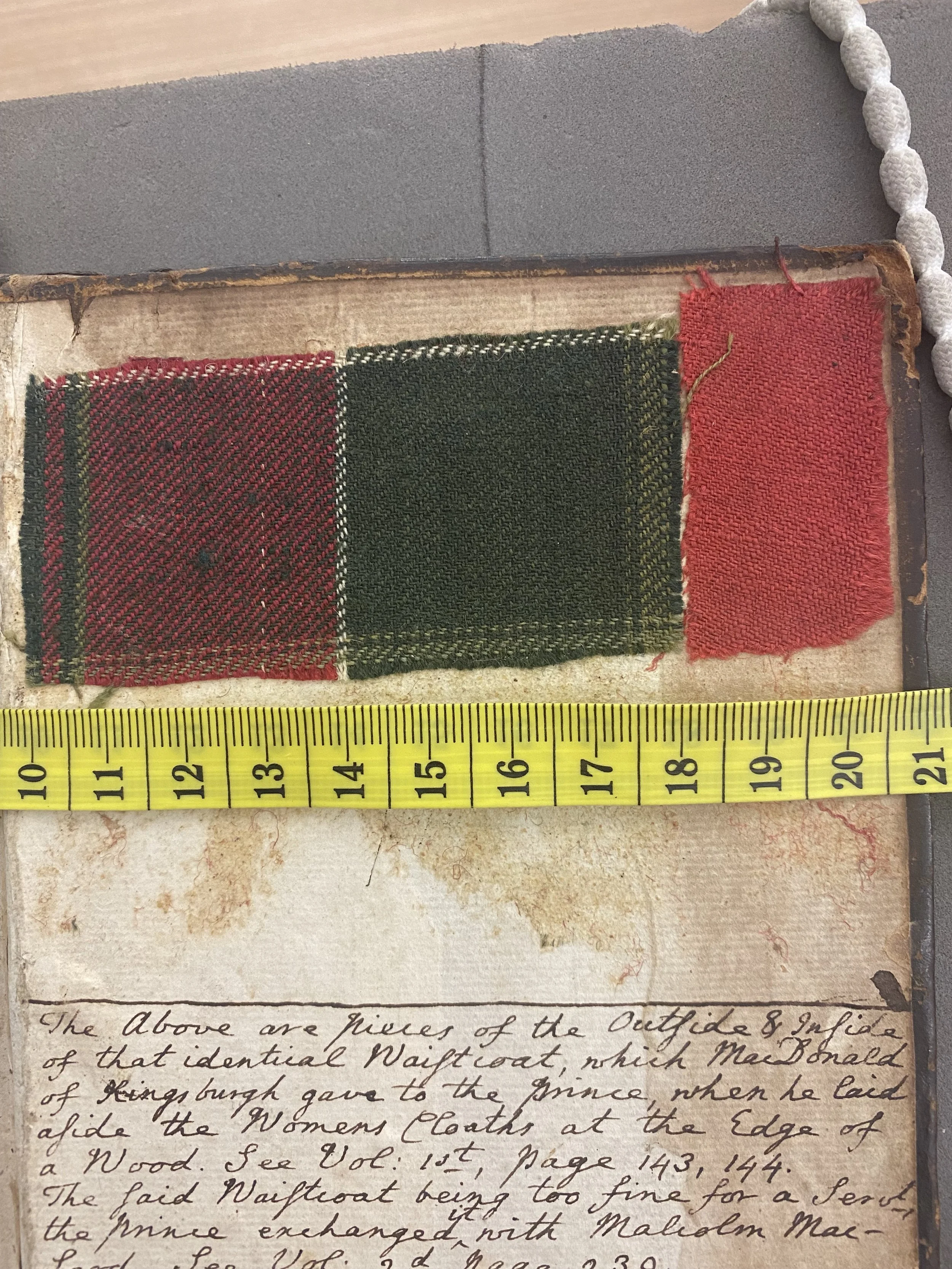

It is unknown what Prince Charles Edward’s waistcoat and small clothes – the 18th century term for breeches- would have looked like. However, given that it is known that he wore clothing made from hard tartan throughout the ’45, it would not be unreasonable to make these items from a similar tartan.

Fig.16: James Worsdale, Prince Charles Edward Stuart, son to the Pretender, 1745, Harris Museum & Art Gallery, PRSMG : P1820. Accessed from https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/prince-charles-edward-stuart-17201788-son-of-the-old-pretender-152563 on 5th April 2024.

Figure 17: Extant piece of Macdonald of Kingsburgh tartan worn by Prince Charles Edward Stuart in July 1746. Provenance: Macdonald of Kingsburgh to Bishop Robert Forbes. Preserved inside the back cover of volume 3 of Lyon in Mourning. Photo by Jo Watson, 2023 with full permission of the National Library of Scotland.

There is some tartan which is known was worn by Prince Charles Edward after he left Kingsburgh, a piece of which is preserved on the inside cover of volume 5 of Lyon in Mourning. It actually does bear some resemblance to the (rather badly) painted tartan in the above portrait. It is a piece of hard tartan which was provided by Anne MacAllister for the prince to get changed into after leaving Kingsburgh House, and is now known as the Macdonald of Kingsburgh tartan. It was actually from one of her husband’s suits, Ranald MacAllister of Skirinish, and not Kingsburghs. It is woven today with a thin yellow band instead of light green, however tartan historian Peter Macdonald has reproduced this tartan which I purchased for this project.

Further reading

Fraser, Flora (2022) Pretty Young Rebel: The Life of Flora Macdonald London: Bloomsbury

Novotny, Jennifer (2013) Sedition at the Supper Table: the Material Culture of the Jacobite Wars, 1688 – 1760. PhD Thesis, University of Glasgow. Accessed from https://theses.gla.ac.uk/4659/ in 2022.

[1] Lyon in Mourning can be accessed online here: https://digital.nls.uk/scottish-history-society-publications/browse/archive/128333222#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=362&xywh=-321%2C-1%2C2348%2C2845

[2] About ‘stuff’ https://thedreamstress.com/2014/08/terminology-whats-the-difference-between-worsted-woollen-wool-fabrics/